A Cowboy Outfit De Luxe

Tracking the Construct of Canadian Cowboy Culture through 40 years of Eaton’s mail-order catalogues.

“Eaton’s catalogues do not reflect Canadian culture; they transmit their ideas about what Canada could or should be, projecting or mapping these concepts on to their viewers, using variations of archetypes and tropes in the same manner as folklore. Understanding Eaton’s as colonial, folkloric, anonymous, and intently designed is essential to place it within Canadian design history”

A large amount of my design research centers on the Canadian mail order catalogue for the T. Eaton department store, and its impact on Western Canadian culture. I am also interested in the many ways that Eaton’s contributed to Canadian design history through the design and manufacturing of objects and products, the design and production of printed catalogues, the design of distribution systems, and its research and development labs focused on material and market research.

One small facet of the culture-designing capacity of this mail order catalogue is the ways in which Eaton’s identified, developed, and sustained Cowboy Culture. Canadian cowboys were rare until the late 1800s, when herds of cattle were bought and driven north from the U.S.

The myth of Canadian cowboy culture, rooted in ranching and raising cattle in Western Canada, became influenced by the folklore of the American Wild West. Canadian cowboys rarely experienced the lawlessness of the American west that led to shoot-outs, skirmishes with Indigenous people, or the creation of mythic heroes and outlaws. Despite all this, the Eaton’s mail order catalogue reinforced a folkloric and, eventually, a cinematic construct of cowboy culture in Western Canada which is still adopted by non-ranchers today. “Eaton’s catalogues do not reflect Canadian culture; they transmit their ideas about what Canada could or should be, projecting or mapping these concepts on to their viewers, using variations of archetypes and tropes in the same manner as folklore. Understanding Eaton’s as colonial, folkloric, anonymous, and intently designed is essential to place it within Canadian design history” (Zabolotney, forthcoming.) This work-in-progress tracks the construct of cowboy culture through approximately 40 years of catalogue design and distribution.

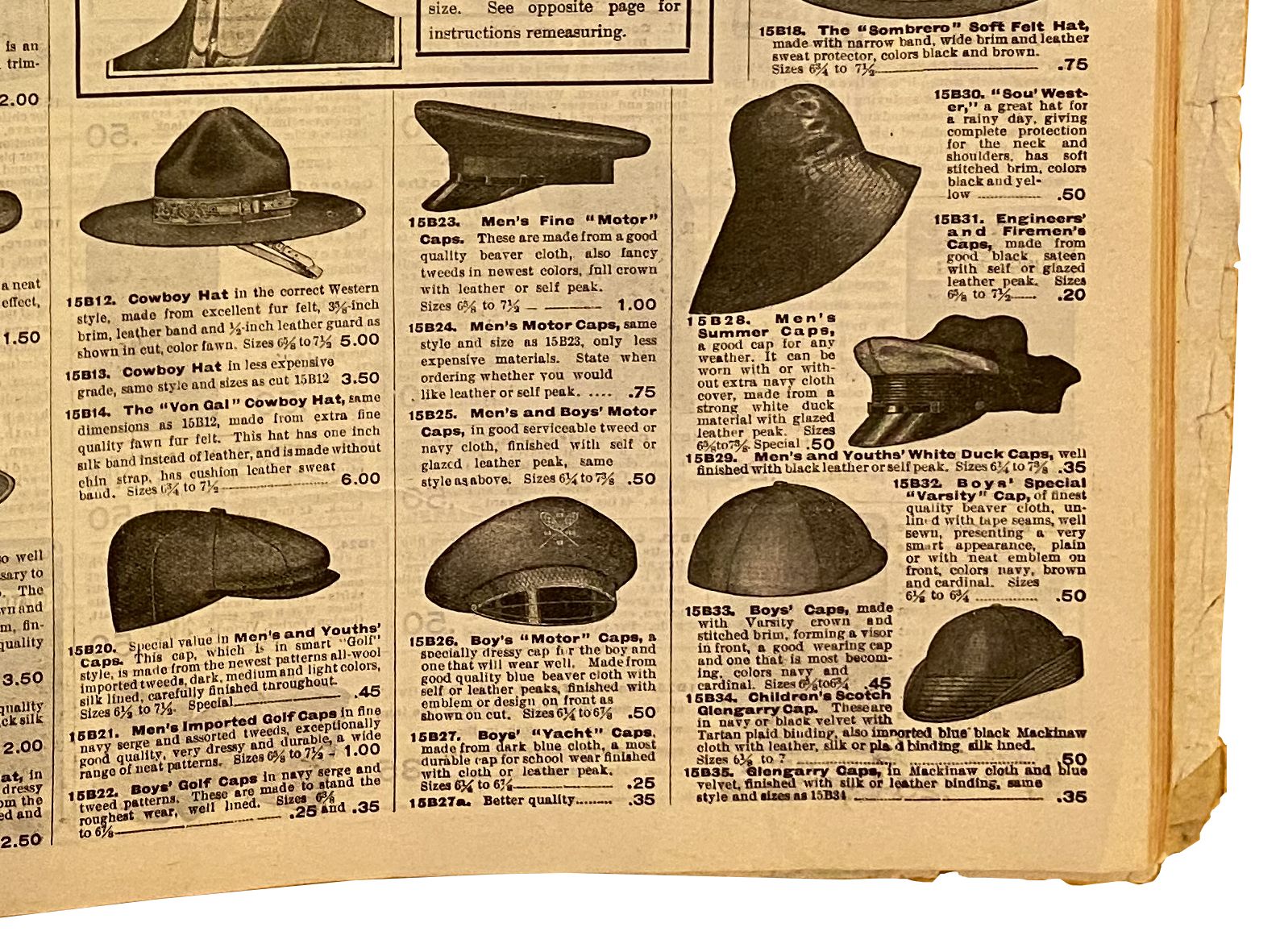

As early as 1910, the commercialization of the concept of cowboy culture began, designating a specific style of hat as a “Cowboy Hat in the correct Western style.”

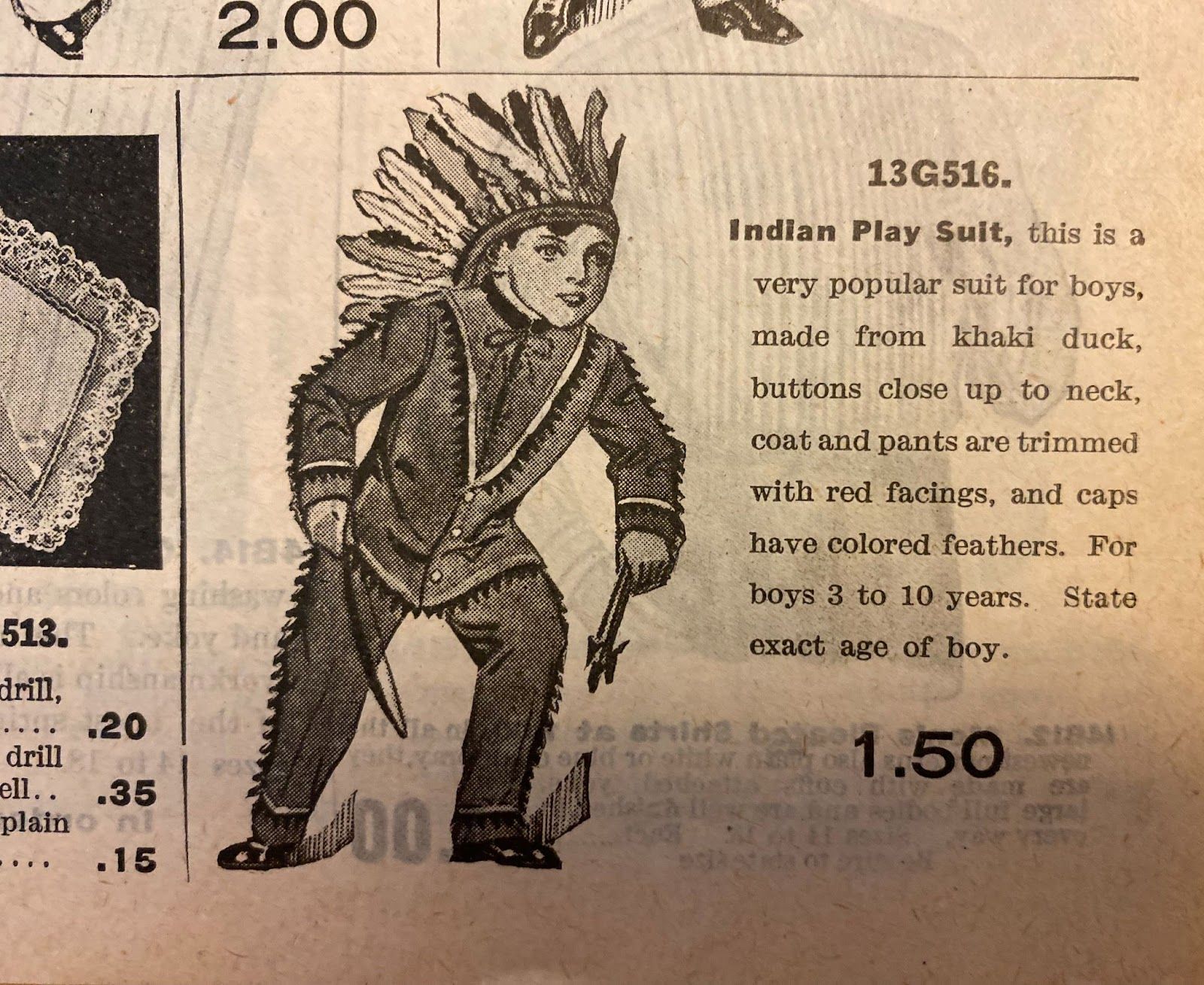

The 1911 issue also sold the same cowboy hat, and added a so-called “Indian Play Suit,” already adding to the unsophisticated diminishing and lack of understanding of Indigenous culture.

These hats and suits continued throughout the early part of the 1900s, adding a “Real Cowboy Suit” in 1916…

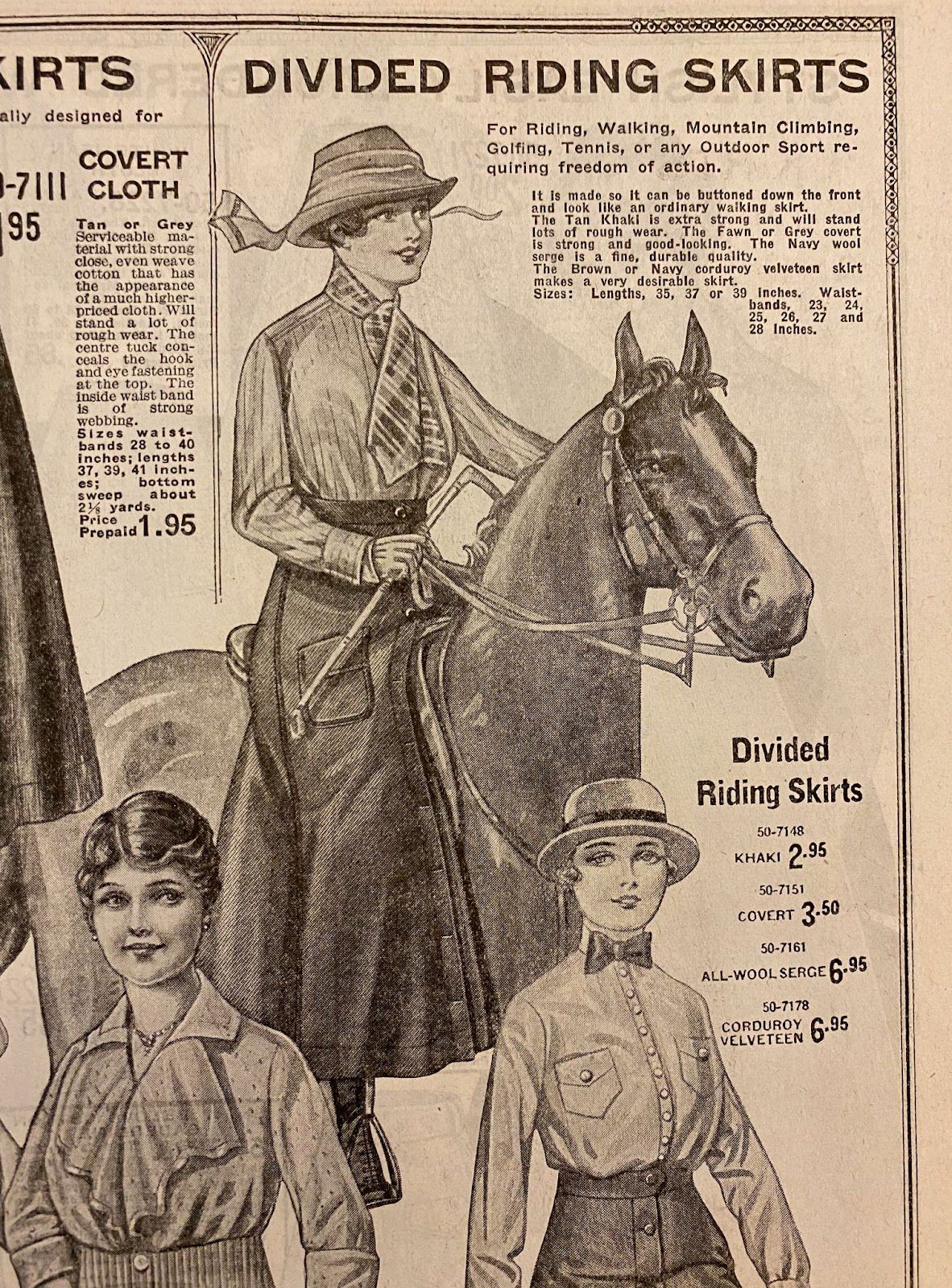

…Divided Riding Skirts for women in 1917…

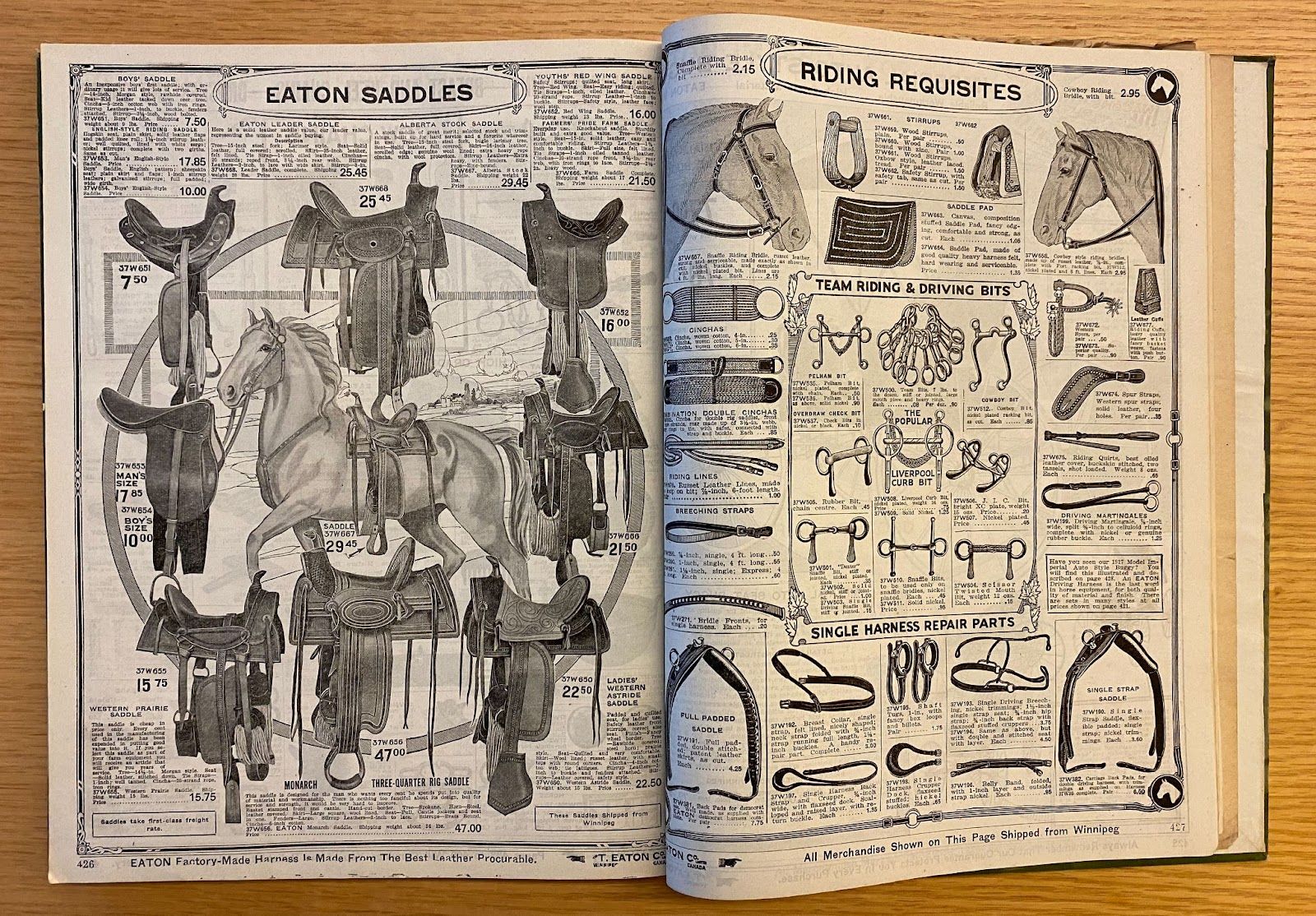

…and Eaton saddles for horses in 1917.

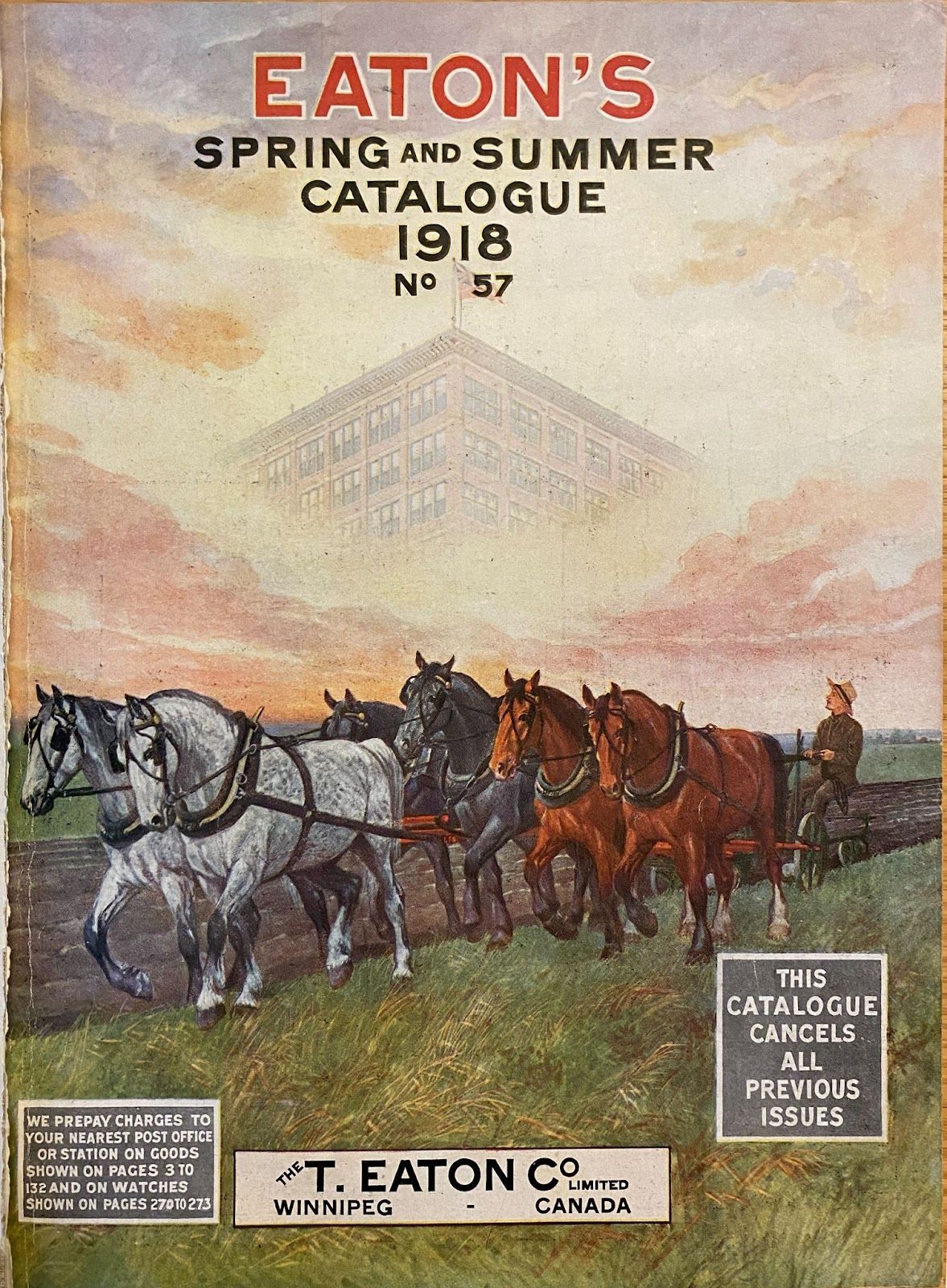

The 1918 cover of the Eaton’s catalogue shows a western scene of breaking the land for farming and ranching, with a vignette of the Eaton’s department store looming over the scene as a harbinger of “progress.”

By 1919, the boy’s “cowboy outfit” was featured on a rare full-colour lithograph printed page. It’s referred to as “the ever-popular play suit of Western boys — a ‘Cowboy’ outfit”. It’s not a costume, but a choice offered on the boys’ clothing pages. The standard accessories to this outfit include a rope and gun in its holster. The gun, of course, is an American influence on Canadian cowboy folklore. It was not a necessary item in Canada. Ranchers may have chosen to bring rifles with them when on horseback, but this was to defend themselves from wildlife, not outlaws or bandits.

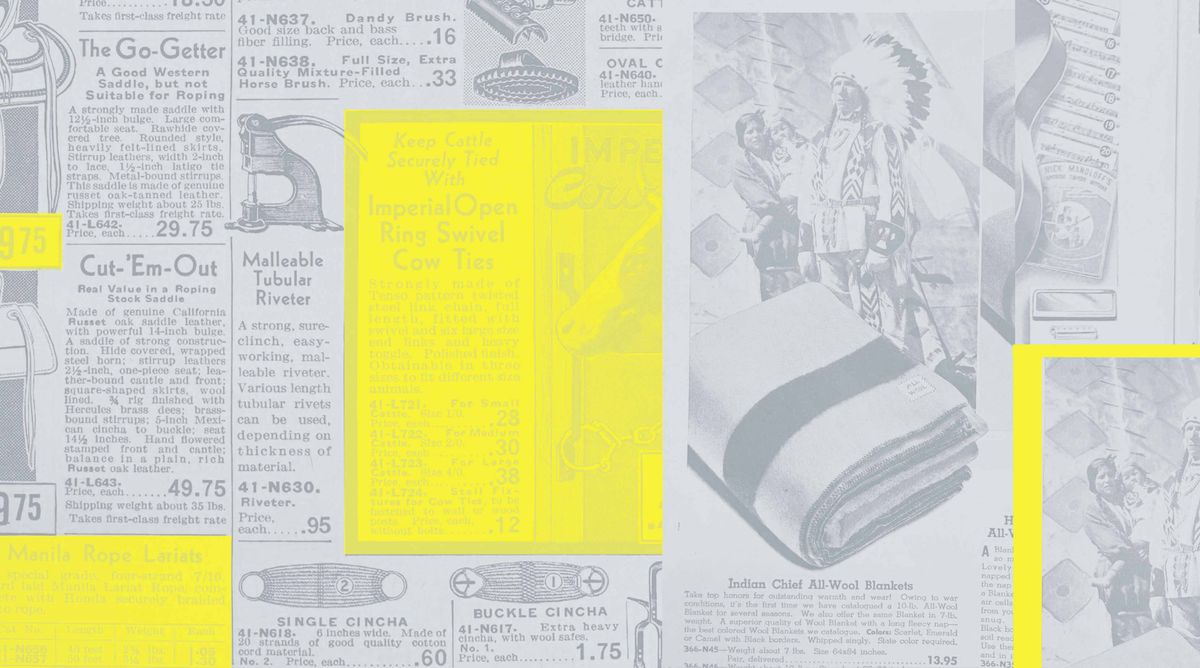

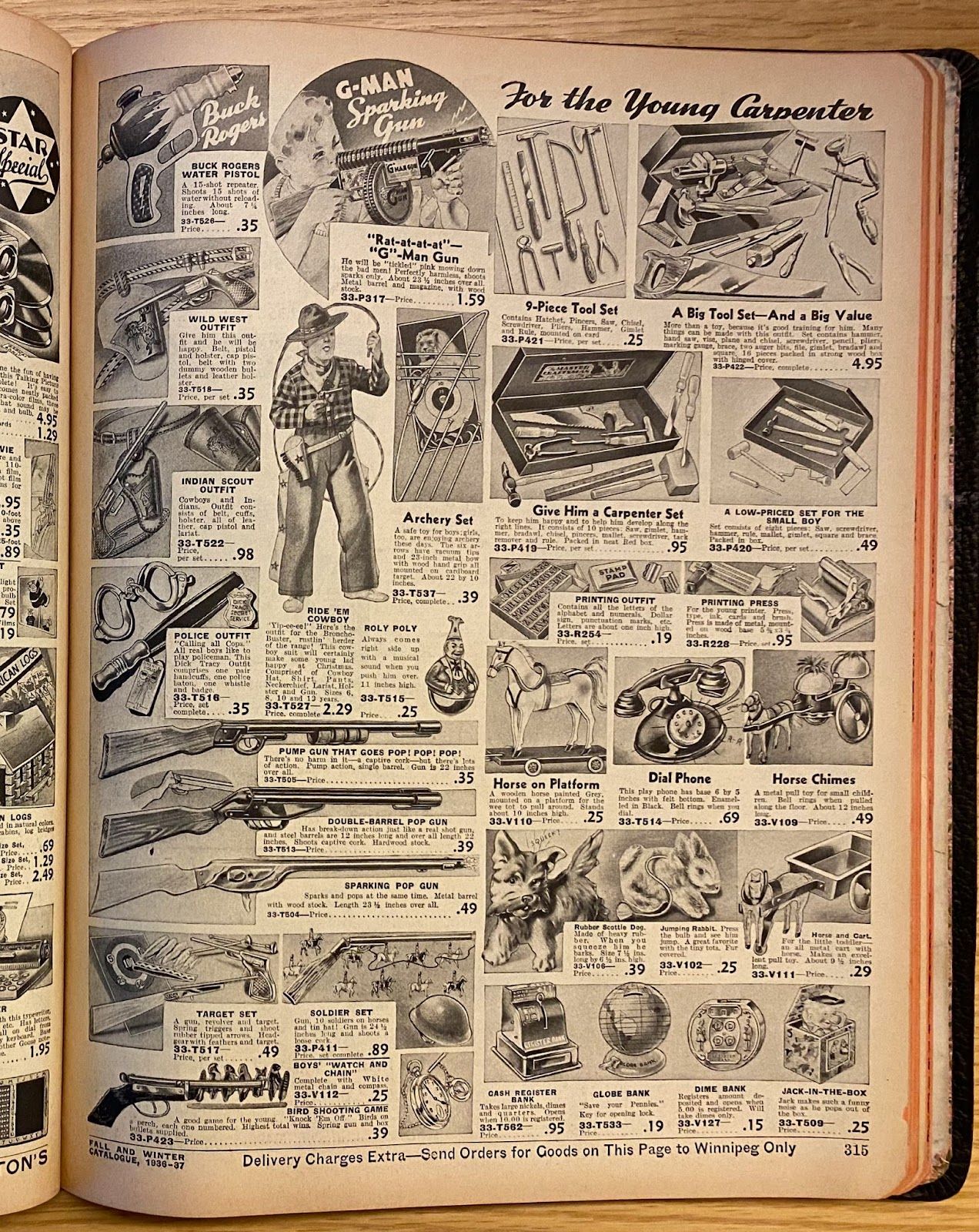

During this time, Eaton’s continued to sell equipment and tools for authentic ranching activities. Eaton’s catalogue issue in 1935 fuses the practical with fantasy of cowboy culture, with an enthusiastic “Ride ‘em, Cowboy!” headline and the serious business of choosing the right horse saddle. This dual nature of serious western equipment paired with a folksy romance of cowboy outfits, toys, and musical instruments.

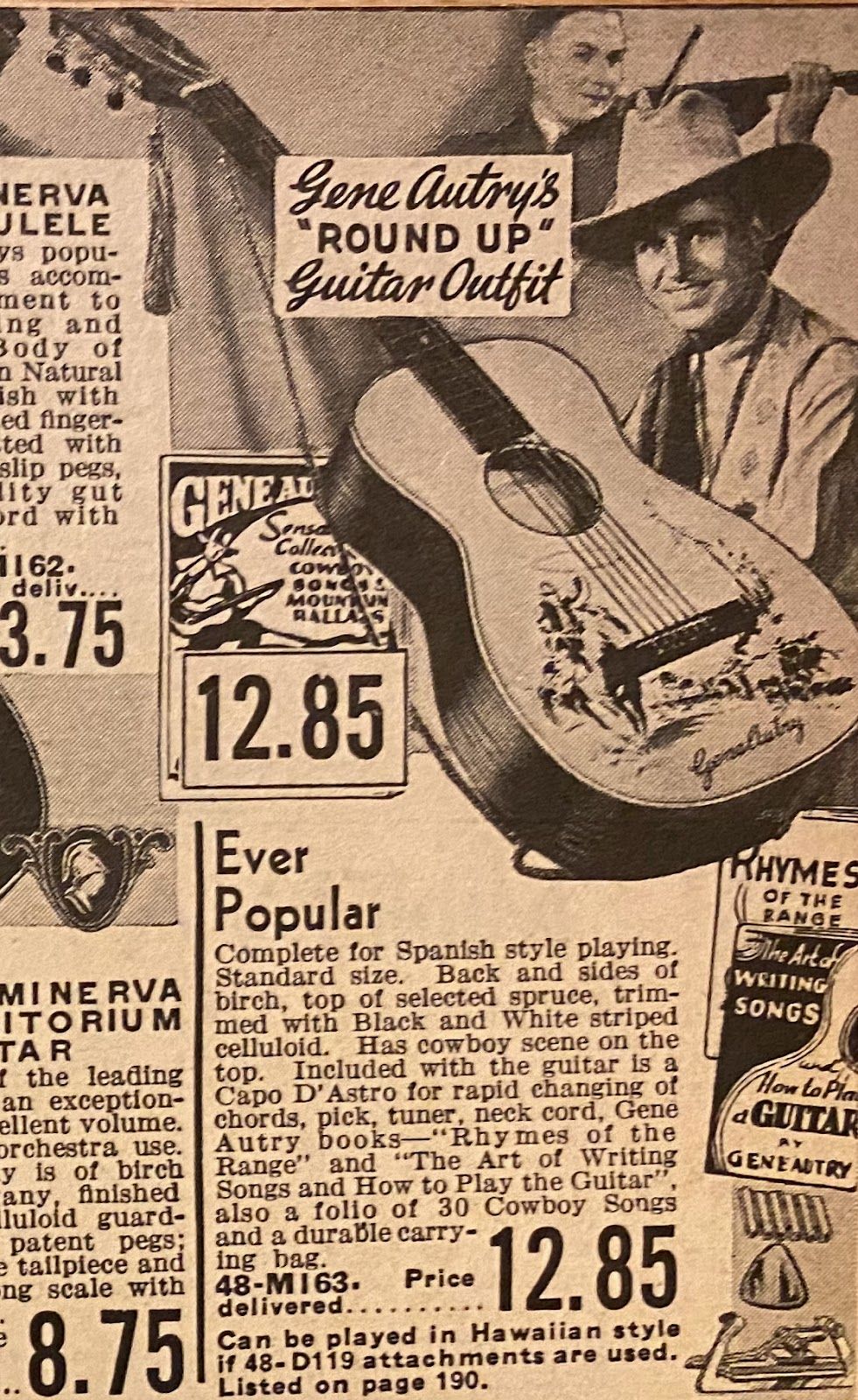

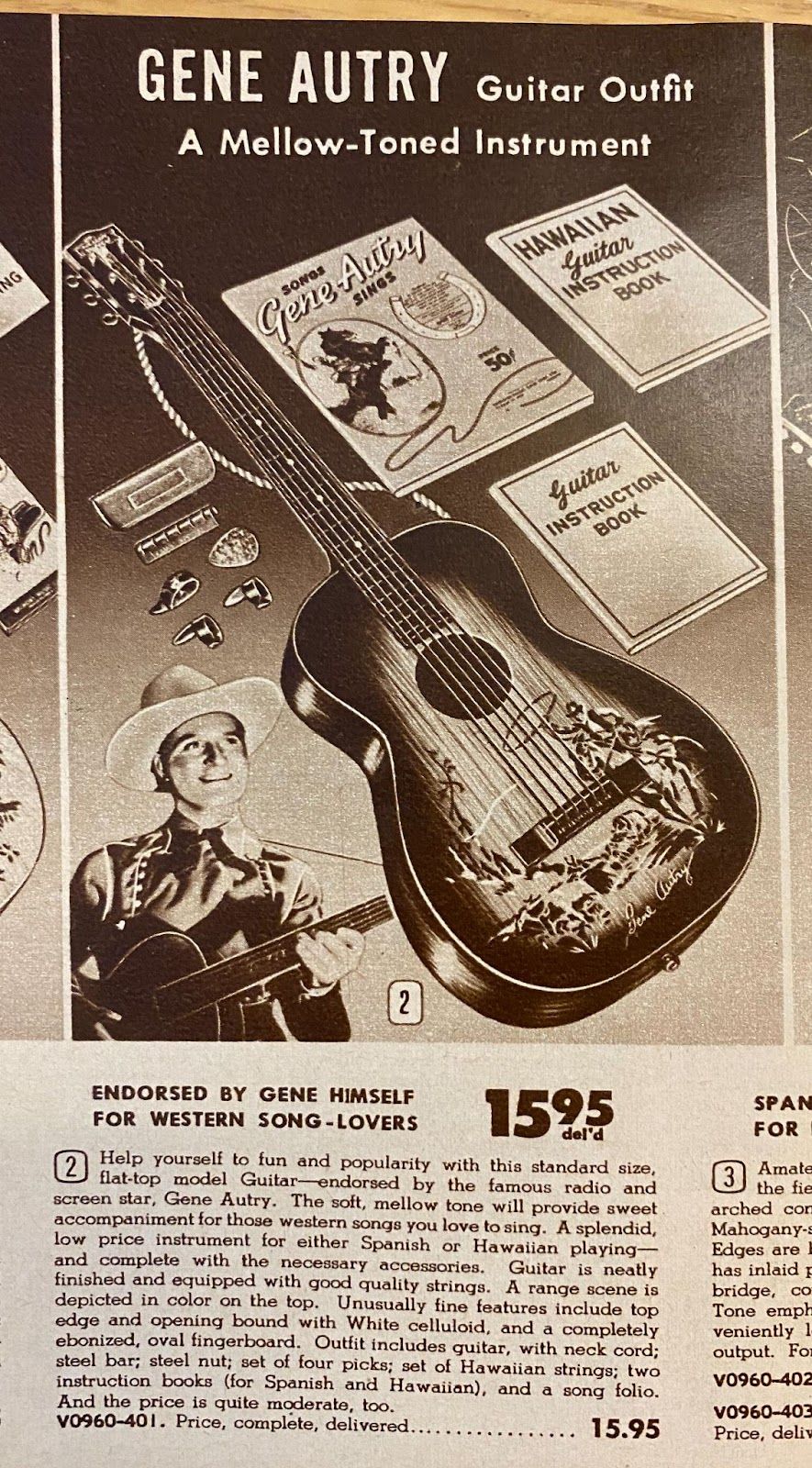

Also in the 1935 catalogue is this first glimpse of Gene Autry’s ‘Round Up’ Guitar Outfit. This guitar and accessories were also found in other American mail-order catalogues at this time. Gene Autry starred in five western movies in 1935, likely viewed in both American and Canadian theatres, fusing Canadian cowboy culture with its American counterparts.

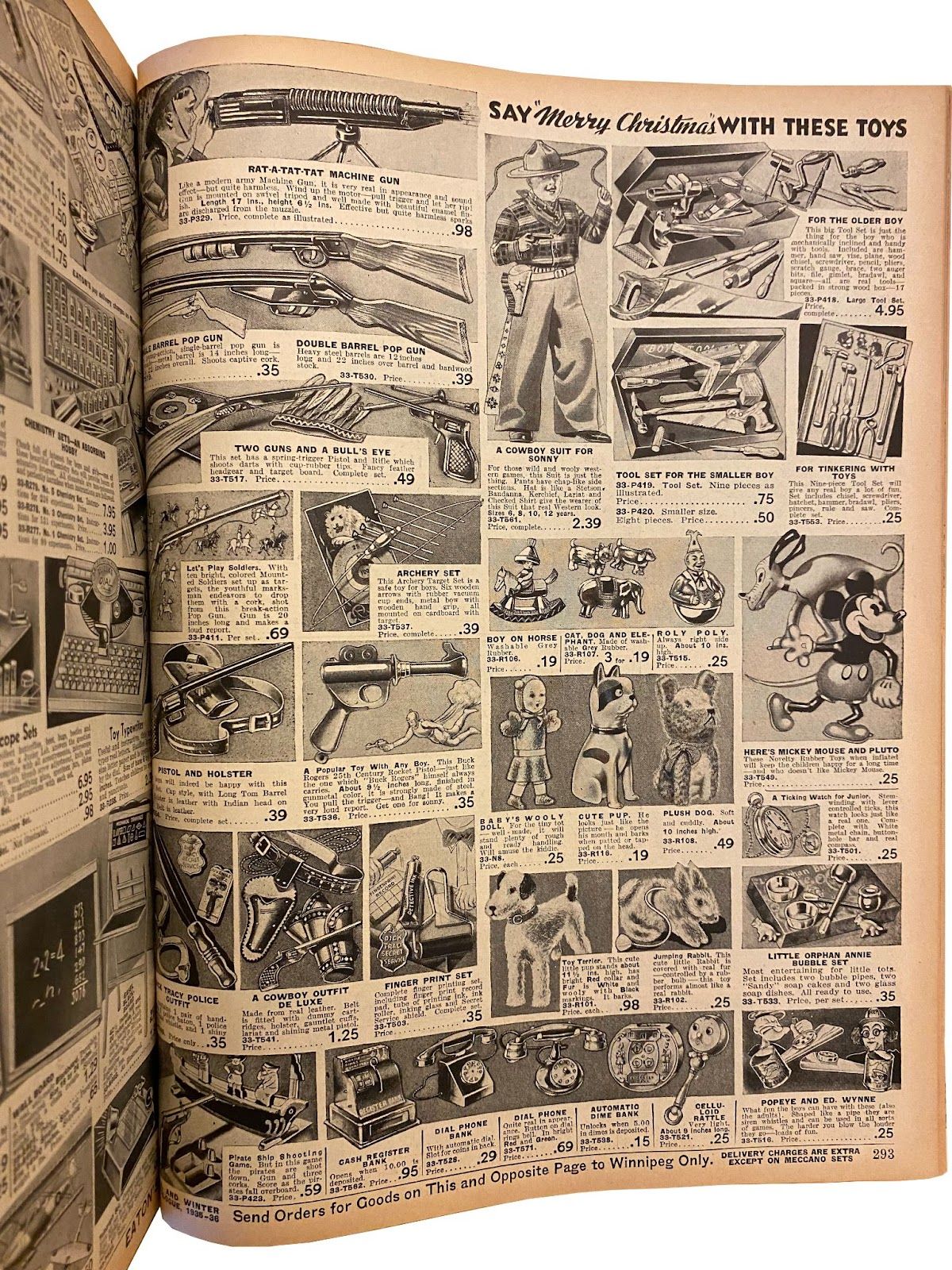

Eatons happily amplified these American transmissions, adding a cowboy suit as a costume in the toy section of the catalogue. “A Cowboy Outfit De Luxe” also echoed the cinematic version of cowboy culture, with a pistol, holster and belt, and leather wrist cuffs.

The same cowboy costume appeared the following year in the 1936/37 Fall and Winter Catalogue, but appears to be redrawn with a new checkered shirt and titled ‘Ride ‘em Cowboy.’ This image sits next to two western gun choices: ‘Wild West Outfit’ or ‘Indian Scout Outfit’.

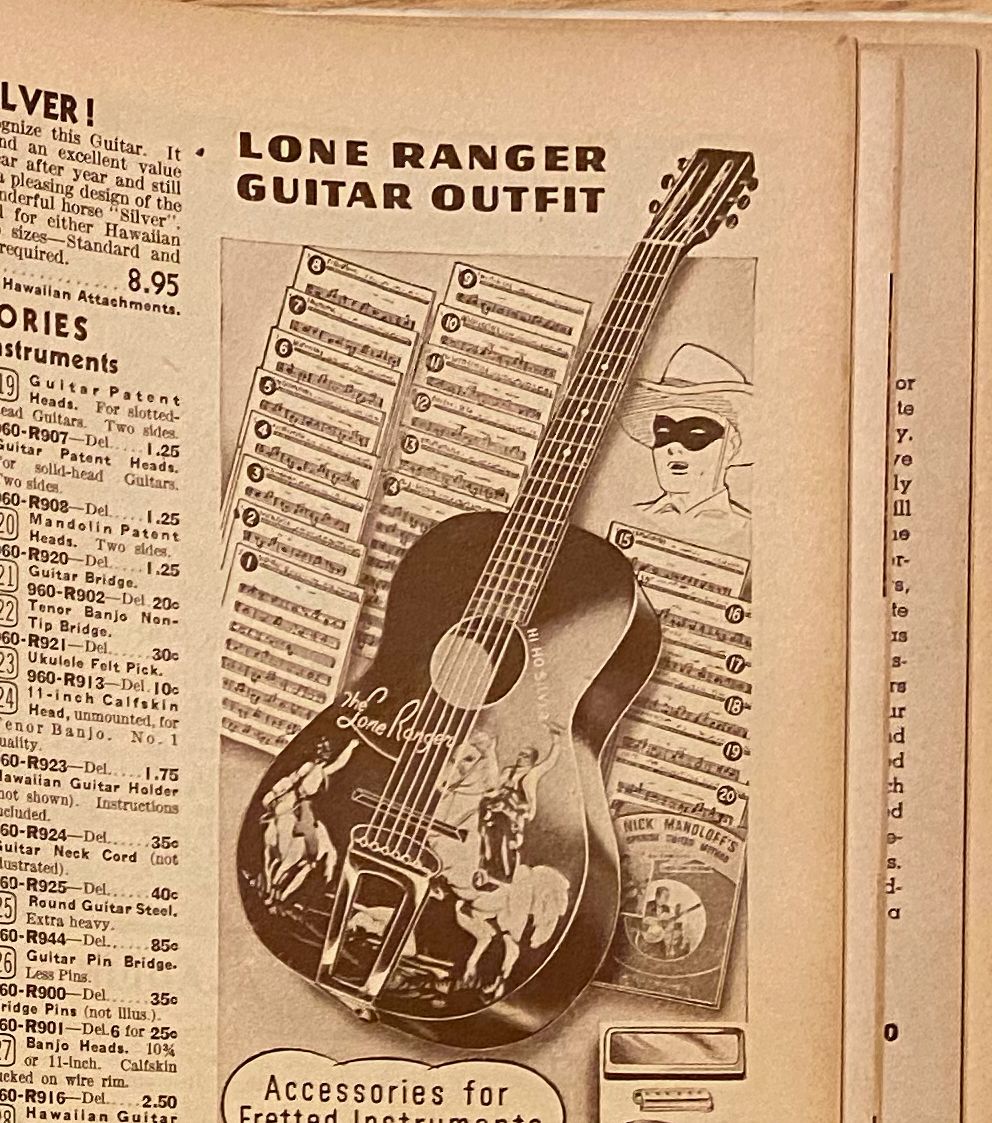

By 1945/46, another screen legend, The Lone Ranger, joins Gene Autry as a motif on a guitar. Unlike Gene Autry, who actually played a guitar and sang, the Lone Ranger is merely an applied decoration, reinforcing a relationship between western music and cowboy culture.

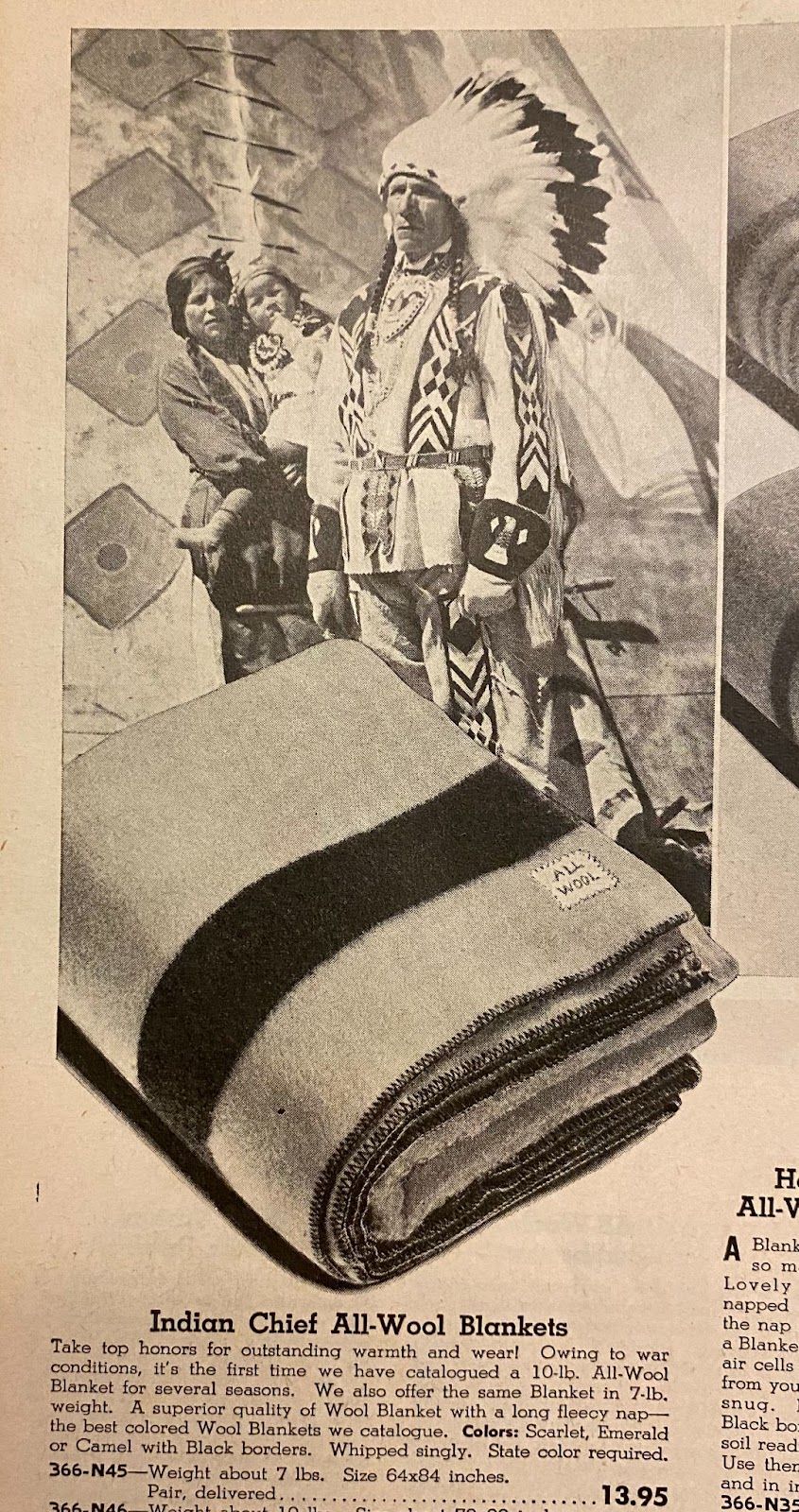

In the same 1945/46 edition, Eaton’s offered a rare image of Indigenous people, representing a ceremonial version of a culture not congruent with the history of western Indigenous people and the Canadian reservation system. During this time, Indigenous people did not have a legal freedom to travel or leave their reservation, leaving them in poverty, starvation, and culturally disconnected from other Indigenous groups throughout Canada. Eaton’s depiction here is simulacrum, with no relationship to its reality at the time. It’s an attempt to romanticize and represent an idea about Indigenous people, whether it was true or not.

Forty years after illustrating, manufacturing, and depicting western goods in their catalogues, Eaton’s reached a stage of nostalgia with cowboy culture. Western films, cowboy movie stars, the stories of pioneers populating Western Canada, and the constant reinforcement of these images in mail-order catalogues became a force of emphasis of this constructed cowboy and western culture.

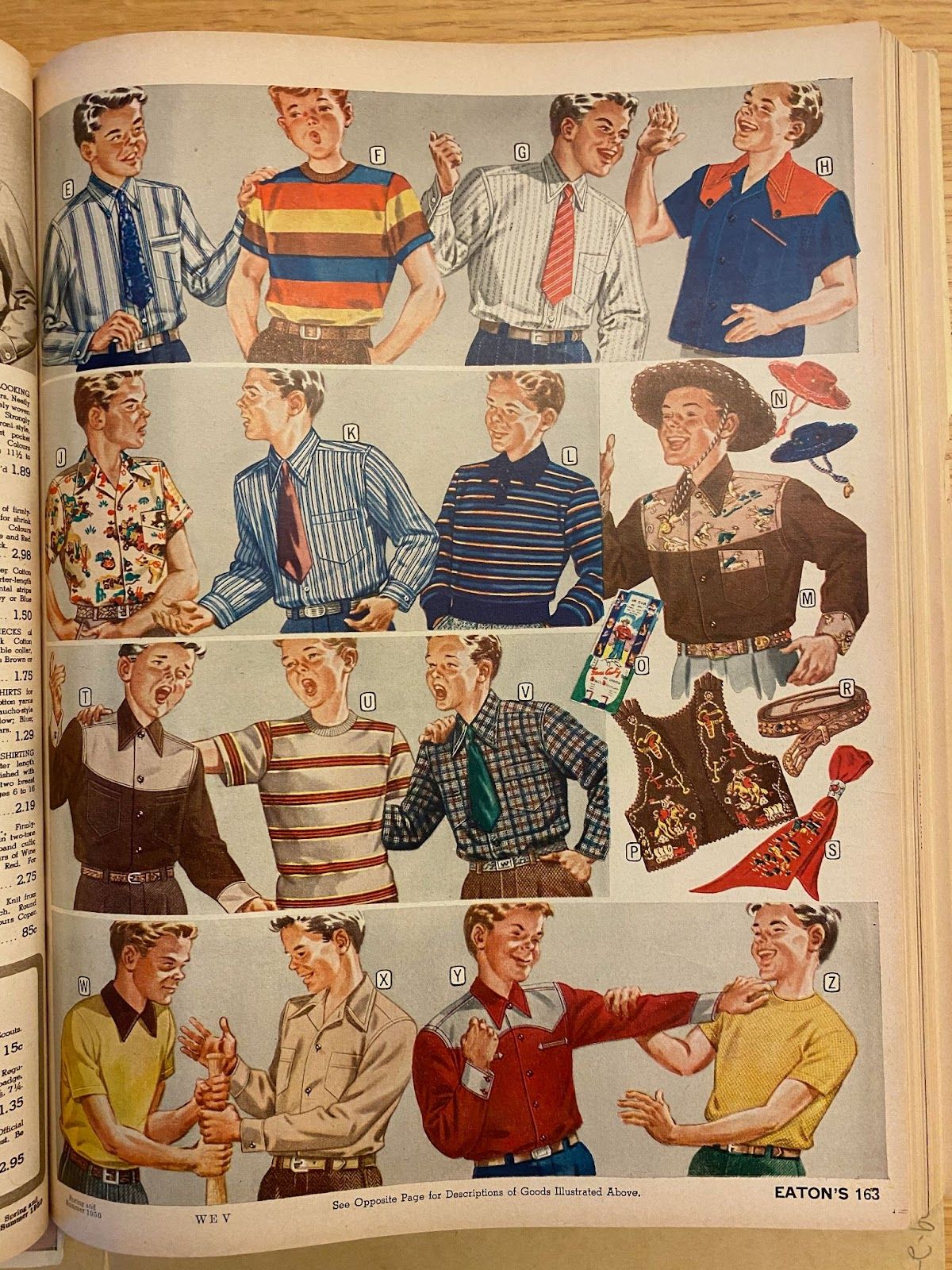

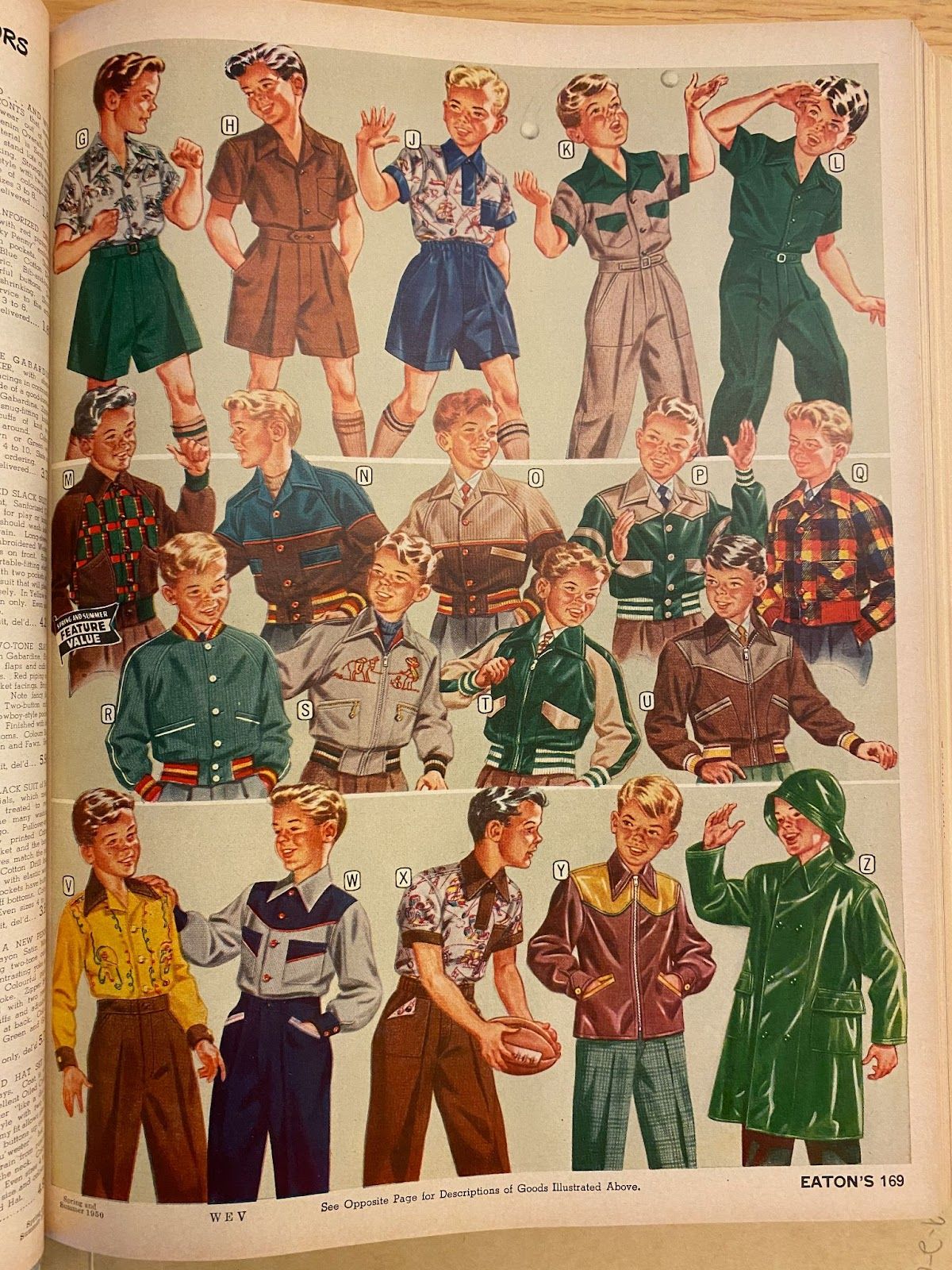

Even if not wearing an outright costume, or costume accessories, shown in this 1950 edition, several shirts and jackets show a Western style of yoke – contrasted in colour, often with a pointed dip on each chest, along with a highlighted trim on the pockets. This style does not lend any practicality to the daily tasks of any true cowboy, but becomes an iconic indicator of cowboy culture — a cowboy enthusiast.

By this time, the Gene Autry guitar continues to sell, after being featured in Eaton’s catalogues for over 15 years. The 1950s version appears to offer a few more additional items, such as thumb picks and instruction booklets, but remains relatively the same.

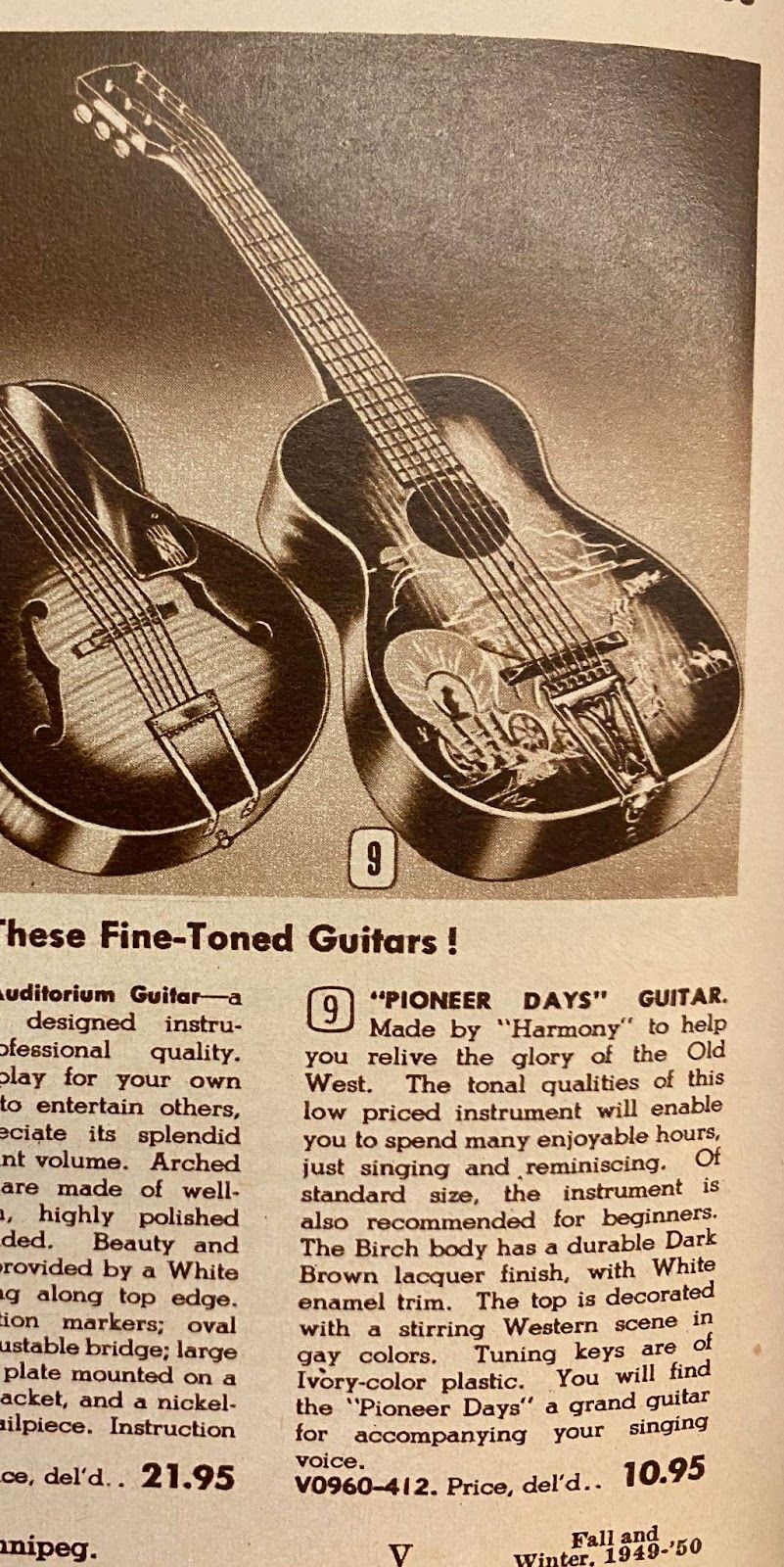

Along with the Gene Autry guitar, however, is the “Pioneer Days” guitar, “to help you relive the glory of the Old West.” This nostalgia reinforces the myths of Western culture in Canada and blurs the lines between real memories and the adventures told to viewers on films, in books, and over the radio.

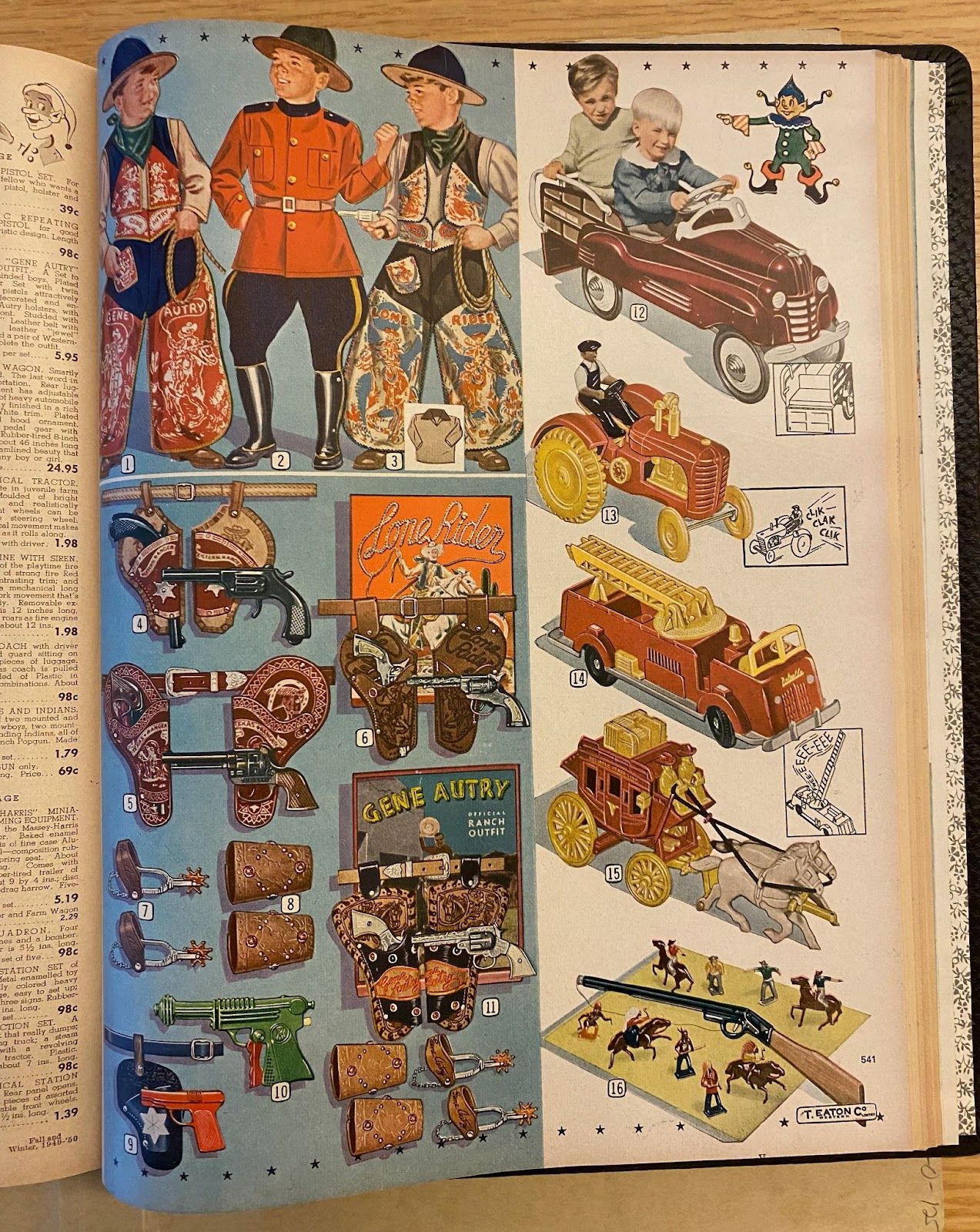

Cowboy costumes and toys continued to dominate the catalogue section for children as well in 1950, in full colour.

Eaton’s contribution to the construction and reinforcement of cowboy culture does not stop at 1950. This work in progress shows the progression of cowboy culture from the practical settler needs towards a cultural echo that requires a multi-modal approach to consumption. Eaton’s catalogues are a designed system — the production and manufacture of items, designed into a large-scale communication system. While it may not have been called “design’ in the first half of the 20th century, the production and distribution of catalogues demonstrates innovation, creativity, and intent — aligning with contemporary practices in design.